MURYOKO

'Infinite Light'

Journal of Shin Buddhism

John Paraskevopoulos & George Gatenby

A Primer of Shin Buddhism

Originally published in 1995 by © Hongwanji Buddhist Mission of Australia

(Free copies of this publication are available on request)

Contents- Preface

- A Brief Outline of Shin Buddhism

- Who is Amida? What is the Pure Land?

- What is Shinjin?

- What is Nembutsu?

- What is the Mappo?

- Do Shin Buddhists Practice Meditation?

- What is a Bodhisattva?

- The Law of Karma

- Conclusion

Preface

The Buddha's teaching of the way for all beings to attain genuine freedom from anxiety and suffering is affirmed in the Shin interpretation of the Pure Land path. This joyful fact has been experienced by millions of Buddhists for over two and a half thousand years and is a living reality today.

This introduction is in two parts. The first is a brief outline of the main tenets of Shin Buddhism and the second follows up on some of the themes in the first half about which readers may have further questions.

We are happy to be of assistance to readers and invite you to write to us if you have anything more you would like to discuss.

All quotations from the writings of Shinran (1173 - 1262) are taken from the Shin Buddhism Translation Series published by the Hongwanji International Center.

A Brief Outline of Shin Buddhism

For Shin Buddhists, the true nature of things is a lively wisdom and compassion that resonates in the lives of ordinary people. This wisdom and compassion takes form as Amida Buddha.

'Amida' is a compound East-Asian word derived from two Sanskrit words: Amitabha (Infinite Light) and Amitayus (Infinite Life). Sanskrit is the classical language of India where Buddhism first arose. 'Amida Buddha', means, therefore, 'Infinite Light Buddha' and 'Infinite Life Buddha'.

Amida is not limited to a specific point in history although knowledge of him first arose from Shakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism, who appeared in India in the sixth century B.C. Shakyamuni gained enlightenment after a long quest for the solution to the problems of spiritual evil and suffering in the world.

As a result of his enlightenment, Shakyamuni was able to address the needs of each person who came to him to listen to his teachings. To ordinary people, especially those who were unable to follow him in his monastic way of life, he explained how Amida Buddha could bring everyone, without exception, to Buddhahood which is the highest level of human fulfilment.

The final objective for Buddhists is to become a buddha because buddhas have perfect understanding, are completely free of attachments and therefore always act in ways that are genuinely beneficial. This objective meets the highest aspiration of the human heart. We remain spiritually and morally immature and ill-at-ease until we are fully developed and perfected buddhas, full of love, kindness and freedom from fear and anxiety - transcending the thrall of birth and death.

In the Larger Sutra on Immeasurable Life, Shakyamuni explained how a monk called Dharmakara ('Dharma Treasury') made vows to lead all beings to enlightenment by creating a Pure Land, a realm that is free from the misleading ignorance that hinders our progress to Buddhahood, and how he would enable us all to be born there. Furthermore, Shakyamuni explained that Amida has attained enlightenment in the deep boundless past and has achieved his purpose for us.

Amida also made vows in relation to us, people stranded in the realm of ignorance. These are the vows of infinite light and infinite life.

Light is wisdom, and life is the compassion that results from perfect wisdom. Amida Buddha's understanding is so complete that when he thinks of us he knows us exactly as we are and, indeed, accepts us as we are because of his perfect wisdom.

So it is that the proximate focus for Shin Buddhists is nembutsu, the Name of the Buddha, Namu Amida Butsu, which means "I take refuge in Amida Buddha". Shinran gives a very succinct definition of Shin Buddhism which we find in several places, for example in his poems (wasan): "Nembutsu jobutsu kore Shinshu"; "Attaining Buddhahood through the nembutsu is the true essence (Shinshu) of the Pure Land way" (Hymns of the Pure Land 71).

Amida vowed that his Name would be heard "throughout the ten directions," (Larger Sutra 7) that is, everywhere, and that those who say his name, entrusting themselves to him, will be born in the Pure Land and attain Buddhahood (ibid.).

Although the names of ordinary people can have immense power, Amida Buddha's Name has limitless power. The name of someone we love may evoke fond memories and longing but the Name is Amida Buddha - active in our lives and our consciousness. All of Amida Buddha's virtues, his Life and Light, are embodied in his Name.

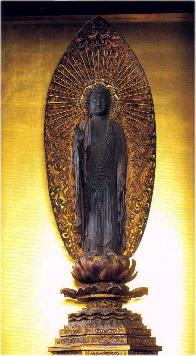

Namu Amida Butsu is the Japanese pronounciation of the original Sanskrit phrase, Namo'mitabhaya buddhaya, which was also transliterated into Chinese characters and pronounced Namo 'mito fo. The six Chinese characters are still the main written form of the principal image in Shin Buddhist temples and home shrines. Indeed, the correct iconic representation of Amida Buddha is really his written Name: Namu Amida Butsu. In Shin Buddhism, if statues and pictures of Amida Buddha are used, these are actually graphic representations of the Name.

In fulfilment of Amida's vow that his Name would be heard everywhere, Shakyamuni praises his Name in over two hundred sutras but especially the three Pure Land sutras which form the basic canon of Shin Buddhism. Those who accept Amida's 'Primal Vow' say the Name in gratitude for the remainder of their lives. The term 'Primal Vow' refers to the totality of all of Amida Buddha's vows but focuses mainly on his vow that those who sincerely and calmly entrust themselves (shinjin) will attain Buddhahood. This is the eighteenth of his forty-eight vows.

Nembutsu people live in the Light and Life of Amida Buddha

and see their own reality as distinctly different from his. Because Amida is

fully enlightened, we become ever more deeply aware of our own profound

ignorance: a kind of blindness which is a sense of being trapped and unable to

overcome the evil oppression of our ego-centricity.

Nembutsu people live in the Light and Life of Amida Buddha

and see their own reality as distinctly different from his. Because Amida is

fully enlightened, we become ever more deeply aware of our own profound

ignorance: a kind of blindness which is a sense of being trapped and unable to

overcome the evil oppression of our ego-centricity.

Although we may practice meditation and seek to control our desires in order to free ourselves, we begin to become aware of the intractable nature of our karmic evil and of our bondage to self-centredness. Even the good we do can become a source of spiritual pride and arrogance that may frustrate any progress we make. Shin Buddhism encourages us to heed the bidding of Shakyamuni in the Larger Sutra, and to relinquish all of our spiritual needs to Amida Buddha. In so doing we accept the Vow (will, mind or intention) and the Name of Amida ("Namu Amida Butsu") and, therefore, our ultimate destiny - Buddhahood, Nirvana. When this happens, our life becomes a joyful adventure, characterised by a sense of indebtedness.

The difficulty many of us have is in accepting that we are really taken in by wisdom and compassion just as we are: unable to become good or better people. All of us have an unendurably painful dark side: deep and terrible greed and anger. Worse, we are profoundly ignorant and constantly shocked at our own insensitivity. Within ourselves, we discover the existential pain that afflicts us all in this "Last Dharma Age", the age of mappo.

Yet the nembutsu can be with us in all situations, joyful or painful, without exception. This is why Amida has given us his Name. This is why his Primal Vow is also called "The Universal Vow". Shinran refers to the Primal Vow as the "Great Ocean" because it takes in and accepts all people, no matter who they are, just as countless life-forms live in, and depend upon, the ocean. Shinran demonstrated from the writings of Mahayana sages, down through the ages, that nembutsu is "the call of the Vow that commands us to trust it". (Kyogyoshinsho II.34).

Shinran's personal teacher, Honen, said in his major work, Senjakushu, that the nembutsu is the supreme teaching of the Mahayana because it is easy to keep in mind and easy to say; accessible to all people without exception. The person whom Amida accepts in his Great Vow is not the person we show to the outside world but the person even we ourselves would rather not see.

The person who awakens to Amida's Mind - in other words, accepts the Primal Vow - is born in the Pure Land. However, since the time of the great Shin Buddhist master Shan-tao, who lived in seventh-century China, it has been clearly understood that the Pure Land is, in fact, Nirvana or Buddhahhood - ultimate realisation of transcendence; in Buddhist terms "extinction of birth and death".

A Buddha is free of all attachment and aversion and has realised the true nature of things: wisdom and compassion. For this reason, he or she understands other people perfectly and moves to free them from the delusions that keep them in suffering and anxiety. So it is that our goal does not end in self-absorbed bliss but in reaching out to others to help them as well. In the way that Shakyamuni returned to ordinary human society after his Enlightenment, Amida Buddha initiated - in his Twenty-second Vow - our "return" (genso) to this world, so that we may become active in leading others to Enlightenment "so that the boundless ocean of birth-and-death be exhausted". (Kyogyoshinsho VI. 118)

This has been a very brief outline of some key points in Shin Buddhist teaching. However, the Shin Buddhist way of developing a genuine understanding of the teaching is through "hearing the Dharma"; (monpo). We must "hear" the cause and result of Amida Buddha's Primal Vow.

In order to "hear", we should study Shin scriptures and listen to Shin teachers. We listen for deep meaning and do not merely cling to the words. Although language is an important vehicle in conveying the teachings, it can be ambiguous and misleading when dealing with subtle and profound realities. This is why every school of Buddhism insists on a thoughtful approach to life.

Who is Amida? What is the Pure Land?

Amida (Amitabha in the original Sanskrit) is the

Buddha of Infinite Light and Eternal Life. He is a manifestation of the absolute

and supreme reality which is known in Mahayana Buddhism as the Dharmakaya.

The Dharmakaya completely transcends time and space but is also, at the same

time, to be found in all things and within all sentient beings. It constitutes

the fundamental essence of all existence and possesses, pre-eminently, the

qualities of absolute wisdom, compassion and bliss. It is the principal aim of

Mahayana Buddhism to ultimately attain, for oneself and others, blissful and

eternal union with this reality - a state more commonly referred to as Nirvana.

Amida (Amitabha in the original Sanskrit) is the

Buddha of Infinite Light and Eternal Life. He is a manifestation of the absolute

and supreme reality which is known in Mahayana Buddhism as the Dharmakaya.

The Dharmakaya completely transcends time and space but is also, at the same

time, to be found in all things and within all sentient beings. It constitutes

the fundamental essence of all existence and possesses, pre-eminently, the

qualities of absolute wisdom, compassion and bliss. It is the principal aim of

Mahayana Buddhism to ultimately attain, for oneself and others, blissful and

eternal union with this reality - a state more commonly referred to as Nirvana.

In itself, the Dharmakaya remains unknowable and imperceptible to our ordinary human faculties of sense and cognition. One can only be made aware of it through prajna which is an intuitive power capable of seeing things as they are, undistorted by the influence of ignorance and the myriad passions that afflict us constantly. As only very few people have had the capacity and strength to cultivate prajna through meditation and other practices, the Dharmakaya, in its dynamic compassion, has chosen to manifest itself in a form more readily accessible to the multitudes of suffering and ignorant beings - a form that allows all people to share in its inexhaustible blessings, wisdom and power. This form is Amida Buddha.

Amida Buddha and the Dharmakaya are, in fact, identical, differing only in function. One could say that Amida Buddha is the 'personal' face of the formless Absolute and the only medium through which ordinary beings can ever get to know its treasures. In this sense, the revelation of Amida Buddha to the world can be seen as an act of compassion which serves to illuminate one's path in this turbid world of birth-and-death (samsara).

In Mahayana Buddhism, the Buddha is said to possess three bodies. This is the doctrine of trikaya. The first body is the Dharmakaya of which we have already spoken. The second, the Sambhogakaya, is any manifestation of the supreme reality in the transcendent realm that serves as a tangible object of meditation or worship - Amida Buddha, for example. There are also many other Buddhas that serve this function but Amida remains pre-eminent for reasons that will become apparent later. The third body, the Nirmanakaya is, in turn, a manifestation of the higher bodies and takes the form of Buddhas and sages in the physical world where the greatest number of people might derive benefit from their teaching. The historical Buddha of our era, Shakyamuni (or Gautama) who lived in India, is considered by Shin Buddhists as a manifestation of Amida Buddha revealing the Mahayana sutras to our world - in particular, those concerning Amida Buddha and his Vows.

The story of Amida Buddha is presented in the sutra literature of the Pure Land School. A powerful king, on hearing the teaching of the Buddha, awakens the aspiration for the highest, perfect Enlightenment. He renounces his kingdom and throne and becomes a monk, taking the name of Dharmakara. In his desire to liberate all sentient beings from suffering and delusion, he makes a number of vows (forty-eight in total) in the presence of the Buddha Lokeshvararaja. These vows are aimed at his becoming a fully awakened Buddha and establishing a transcendent realm, the Pure Land, where ideal conditions are to be found for attaining Enlightenment and Nirvana. Through dint of extraordinary Buddhist practices spanning many aeons (such as deep meditation, cultivation of profound wisdom, exercise of selfless compassion, kindness and charity), Dharmakara eventually fulfills all his vows, becoming the Buddha of Infinite Light (Amitabha) whose realm is Sukhavati (Land of Utmost Bliss). Since that time, Amida has led countless beings to his Pure Land through simply having them entrust their salvation and enlightenment to his care.

The story of Dharmakara should not be seen merely as an allegory with a didactic purpose; but it is not necessary to insist that it details a series of historic events, either. Rather, it is an affirmation of the vast processes involved in the task of human transformation and enlightenment. Furthermore, the law of karma dictates that such processes cannot take place independently of the realm of samsara. In the Mahayana understanding of things, Nirvana and samsara are inseparable.

Although the descriptions of the Pure Land that we find in the sutras (eg. jewelled ponds, celestial music, exquisite flowers raining down from the sky etc.) appear too fantastic and incredible, they are none other than a means (upaya) of conveying the blissful and permanent nature of Nirvana - which is quite inconceivable to ordinary people - in terms and images taken from our every-day world that are more familiar to those who are not aware of any other reality. Presented in such a way, the idea of enlightenment becomes a more intelligible and attractive focus of aspiration to those who would otherwise remain baffled by the highly abstruse and abstract notions sometimes employed by Buddhist philosophers. The Buddha employs all means available to him to bring people to an understanding of his wisdom and compassion. The highest realities that can be conceived are often better explained and assimilated through recourse to rich symbolism rather than through literal description which is largely impossible in such matters anyway.

When the tradition speaks of Amida, the Pure Land, suffering sentient beings etc., it should not be thought that it is speaking of fundamentally different things. The Buddha and his land of bliss are essentially one and the same reality, these terms merely designating different functions or aspects of the Dharmakaya. Similarly, Amida and we cannot be said to be separated by anything other than an illusion comprising our blind passions such as greed, anger and ignorance, all of which are karmically determined. Amida's presence lies within the heart of nature and all living beings. This omnipresence of the supreme reality is also called Buddha-nature and it is only in virtue of this very quality that we share with the Buddha that one can speak of the possibility of attaining final union with him at all. For most people, however, burdened, shackled and blinded as we are by our great karmic weight, the realization of this essential identity will not be possible until our complete enlightenment in the Pure Land at the point of death.

The Light of Amida Buddha is infinite because there is nowhere it does not reach and nothing that it does not penetrate, including the darkest depths of our minds and hearts. This light illuminates the nature of the world and helps us recognize the extent of our profound attachment to our own egos and to the real gulf that, in so many ways, separates us from the Buddha. This light also serves to ferry us safely over the stormy waters of our imperfect existence and to purify us of all the defilements that would ordinarily bar our entry into Nirvana.

What is Shinjin?

In shinjin, we are completely embraced by Amida's inconceivable light and suffused with his mind of wisdom and compassion. It is both our total trust in the power of Amida's Vow to save all beings and the recognition that our limited and imperfect ego can contribute nothing to our own enlightenment, let alone that of others. In Shin Buddhism, the arising of shinjin is the sole condition for attaining birth in the Pure Land at the time of death and realizing Nirvana, because it is none other than our awakening to Amida's mind itself within us.

Shinjin is not enlightenment but rather its guarantee in the life to come. The fact that we are embraced and protected by Amida's light does not mean that we are rid of the various blind passions, anxieties and ego-centric tendencies that afflict our daily lives. It does serve, however, to give us a deep insight into the tenacity of these attachments and to recognise them for what they are. With time, this awareness works to loosen the tight grip the ego usually has on our lives without, in any way, eliminating it. This is a natural consequence of recognizing that the only true reality is Amida by comparison to which the endless solicitations of the ego are seen to be only so many ephemeral illusions fated to impermanence. In this sense, shinjin enables one to deal with the vicissitudes of life by giving one access to a greater reality that transcends the unstable flux of samsara and to which we can turn for refuge and illumination.

An important feature of both Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism is the doctrine of anatman or 'no-self' which is the idea that nothing in our empirical self is stable, permanent or enduring and that the fleeting constituents of the ego do not comprise our real self. Shin Buddhism develops the logical implications of this doctrine and insists that we cannot rely on our unreliable and fickle egos (ie. jiriki or 'self-power') to deliver us from the bondage of this very same egoism. The only way out of the self-defeating futility of such efforts, it would seem, is to rely on a power other than one's own, a power that is not subject to the imperfections and weaknesses of the human self. Shin Buddhists call this tariki or 'Other-power' which is none other than the power of Amida Buddha.

When one relies solely on Other-power for one's enlightenment, the influence of the ego is increasingly diminished by a gradual process of attrition as Amida Buddha's Light begins to take hold of one's entire being, sustaining it with its wisdom and compassion. This is not, of course, to say that the ego disappears in such cases - rather one is more aware of it than ever - but that its manifold poisons and distractions no longer constitute a karmic impediment to one's eventual enlightenment because it is Amida that is doing the work for our passage to the Pure Land. By relying thus on the Buddha alone, our realization of Buddhahood is assured since there is nothing that can impede the will and power of the Absolute itself.

So how does one attain shinjin ? Are there any special practices that one needs to undertake? There is no step-by-step formula by which this realization can be obtained since it is not something that we are capable of producing for ourselves. Our only task is to listen to the Dharma, reflect deeply on its teachings and remain mindful of the wisdom and compassion of Amida Buddha. In so doing and if our karma is favourable, we will naturally become receptive and open to the illuminating grace of his Light which embraces all beings without exception. This realization becomes a great source of joy and gratitude, enriching every aspect of our life.

Although the life of shinjin manifests itself in different

ways for different people, it is invariably accompanied by the nembutsu which

involves mindfulness of Amida Buddha and the recitation of his sacred name: Namu

Amida Butsu or Namo 'mitabhaya Buddhaya in the original Sanskrit,

which translates as "Taking refuge in the Buddha of Infinite Light".

The Pure Land tradition considers the Name of Amida to be invested with all the

virtues and power of the Buddha himself, in which the devotee shares and derives

spiritual benefit through the practice of nembutsu.

Although the life of shinjin manifests itself in different

ways for different people, it is invariably accompanied by the nembutsu which

involves mindfulness of Amida Buddha and the recitation of his sacred name: Namu

Amida Butsu or Namo 'mitabhaya Buddhaya in the original Sanskrit,

which translates as "Taking refuge in the Buddha of Infinite Light".

The Pure Land tradition considers the Name of Amida to be invested with all the

virtues and power of the Buddha himself, in which the devotee shares and derives

spiritual benefit through the practice of nembutsu.

The fact that fulfilment of traditional Buddhist meditative practices and ethical prescriptions are not, in themselves, considered a requirement for attaining enlightenment in Shin Buddhism - as such practices rely on the fallible ego for their success - does not imply that they cannot be practiced as a spontaneous act of gratitude to the Buddha. It is not the acts themselves that are important but the attitude in which they are undertaken. People who assiduously absorb themselves in meditation everyday and faithfully keep the precepts in order to 'earn' deliverance, can often be motivated by an obsessive self-concern that may sometimes border on spiritual hypocrisy, whereas the same practices observed in a spirit of selfless gratitude and joy with no thought to any gain are doubtlessly closer to the real spirit of Buddhism.

To fail in one's efforts to live up to the high standards of the Buddhist way of life is not so much a cause for despair as it is an occasion for remorse and deep self-reflection on one's shortcomings and limitations coupled with a profound gratitude to Amida Buddha for a) helping one to realize the distress of our human condition and b) assuring us of his salvation and enlightenment despite our imperfections which we cannot hope to eradicate of our own accord. To be deeply imbued, in this way, by Amida's mind of compassionate wisdom is to live the life of shinjin.

What is the meaning of Nembutsu?

Of all the forty-eight vows made by Amida Buddha, the eighteenth - the Primal Vow - is considered by far the most significant. It is to be found in the Larger Sutra on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life as follows:

> If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten directions who sincerely and joyfully entrust themselves to me, desire to be born in my land, and call my Name even ten times, should not be born there, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment. Excluded, however, are those who commit the five gravest offences and abuse the right Dharma.

Originally, the phrase 'call my Name even ten times' referred to thinking on the Buddha in a general sense (buddhanusmriti in Sanskrit). This gradually developed into the actual invocation of his Name - the nembutsu - which was considered a natural corollary of one's remembrance of the Buddha. As the Sacred Name of Amida Buddha was thought to contain the perfection and virtue of Enlightenment itself, its mere recitation was seen to have the power to bring to Nirvana all those who had complete faith in it.

In the age of mappo, the practice of nembutsu was considered easier to accomplish for ordinary lay people whose weak capacities prevented them from engaging in the more difficult and austere practices of traditional monastic Buddhism. Unlike such practices, the nembutsu was open to everyone because the Name is both easy to say and keep in mind, providing a more universally accessible means by which mindfulness of the Buddha can be maintained by those incapable of the rigours of monastic life.

As the Name was considered to have this great power to effect total liberation from the snares of samsara, Pure Land adepts in both China and Japan would commit themselves to tens of thousands of recitations of nembutsu each day with a view to ensuring that their eventual salvation would be guaranteed. Shinran, the founder of the Jodo Shinshu school of Pure Land Buddhism, came to regard this attitude to the nembutsu as unsatisfactory and inconsistent with the intention of Amida Buddha's Primal Vow as he saw it as yet another form of 'self-power' along the lines practiced by the older schools. After twenty years of monastic discipline at Mount Hiei, stronghold of the Tendai sect, Shinran abandoned this life in frustration, seeing that it could not help one so blinded by evil passions and ignorance as himself. As he considered his own 'self' so thoroughly polluted by the incessant cravings of his ego, Shinran sought refuge in the teaching of 'Other-Power' - namely that of Amida Buddha, in whom he saw as the only hope for his salvation.

It was Shinran's view that to practice the nembutsu as a means of gaining reward was to fall prey to the same limitations that afflicted the traditional 'self-power' schools which advocated taxing meditation, difficult austerities and strict adherence to the monastic precepts. In other words, he did not believe that our limited and conditioned egos could bridge the vast gulf separating the finite self from the Infinite. After all, it would not be in the ego's own interests to want to contribute to its own destruction, which is why recourse to a power that transcends it is required. Therefore, to want to amass innumerable invocations of the nembutsu with a view to attaining birth into the Pure Land is, according to Shinran, to believe that our self-interested acts are actually capable of attaining the same level of enlightenment as the Buddha. To think thus is to harbour the worst of self-delusions since there is absolutely no common measure between the absolute perfection of Amida's Nirvana and the blind, misguided gropings of our impure selves.

The real significance of the nembutsu for Shinran was that its invocation - and the mindfulness of Amida that it expressed - was none other than the manifestation of true shinjin in the hearts of devotees. As shinjin can only be conferred by Amida, to practice nembutsu in the hope of 'producing' it for oneself is futile. Amida's mind is incomparable, inconceivable and inimitable, and its arising in the hearts of deluded beings is a pure grace which no merely human act can contrive. Similarly, no amount of bad karma can thwart the power of the Name as there is no good that surpasses it. To recite the nembutsu in a spontaneous and uncalculating way is to be imbued with Amida's pure mind of shinjin. It is a natural expression of our being embraced by his Light, despite our grave karmic defilements, and of our complete assurance of the eternal bliss of Nirvana when our time comes to leave this world of tribulation and sorrow.

When Shinran declared that the nembutsu was a manifestation of shinjin rather than simply a means of procuring spiritual benefits, he did not mean to suggest that the Name could no longer be regarded as having the power attributed to it by his Pure Land predecessors. The Sacred Name of Amida Buddha is the vehicle by which we are able to transcend the world of samsara and attain perfect enlightenment in the Pure Land. This capacity, seemingly incredible at first sight, is made possible by the fact that the power of the Absolute itself is fully invested in the Name and conferred to those who hear it, believe in it and invoke it with complete faith in its saving power. To simply recite the nembutsu with no other motive than to attain blissful entry into Nirvana for oneself is doomed to failure because the incentive then appears to be solely one of self-gain uninformed by either gratitude to the Buddha or compassion for one's suffering fellow beings. As the nembutsu is not our good but that of the Buddha, it cannot possibly form the foundation for any meritorious act of our own.

When viewed in this way, the number of recitations of nembutsu is not relevant as it is the quality of the faith behind them that is important. Some will feel impelled to say the nembutsu constantly, others again only seldom. It should be noted, however, that invoking the Name, although a very important feature of Pure Land practice, is not the only way in which the nembutsu can be expressed. Chanting the sutras, worshipping and contemplating the Buddha, making offerings to Him etc., can also be considered as forms of nembutsu in which the mind of shinjin may find its expression. In any event, regardless of the form that nembutsu may take, it is always the working of Amida Buddha in us that is the true source of such practice and the ultimate guarantee of its efficacy.

What is the Mappo?

Mahayana Buddhists entertain a qualitative view of time that is envisaged in relation to the lifetime of Shakyamuni. In other words, the spiritual, moral and physical conditions on earth are seen to progressively deteriorate in direct proportion to the time that has elapsed since the Buddha's entry into the Great Nirvana. A number of distinct ages, since that time, are seen to reflect the successive stages in humanity's increasing darkness, turmoil and spiritual incapacity. The Pure Land tradition considers the present period as the mappo or the 'Decadent Age of the Dharma' where - to quote the Great Collection Sutra - "out of billions of sentient beings who seek to perform practices and cultivate the way....not one will gain realization". A further quotation from this sutra will serve to clarify the matter further:

During the first five-hundred year period after the Buddha's parinirvana, my disciples will be resolute in acquiring wisdom. During the second five-hundred year period, they will be resolute in cultivating meditation. During the third five-hundred year period, they will be resolute in listening to the teaching and sutra-recitation. During the fourth five-hundred year period, they will be resolute in constructing towers and temples, practicing meritorious conduct and performing repentance. During the fifth five-hundred year period, they will be resolute in conflict and strife, which will become widespread with the good dharma being diminished....This is now the last dharma-age; it is the evil world of the five defilements. This one gate - the Pure Land way - is the only path that affords passage.

The 'five defilements' referred to above constitute the

distinguishing characteristics of the age in which we currently live. They are

(i) the impure or turbid age in which calamities occur incessantly (ii) impurity

of the view that ignores the principle of cause and effect (iii) the impurity

and defiling nature of evil passions (iv) the degeneration of the minds and

bodies of sentient beings and (v) the shortening of the span of life of sentient

beings as the result of prevailing evil passions and wrong views.

The famous Lotus Sutra also contains a description of the mappo which, in hindsight, has proven to be disturbingly prophetic:

At the horrible time of the end, men will be malevolent, false, evil and obtuse and they will imagine that they have reached perfection when it will be nothing of the sort.

Under such conditions, the degree of spiritual attainment prevalent at the time of Shakyamuni, is no longer considered possible in this age which is so far removed from his immediate presence and influence. Accordingly, the sutras exhort us to take refuge in Amida Buddha who compensates for our shortcomings by enabling us to reach Nirvana solely through the power of his Name, which contains all his merits and perfection.

Do Shin Buddhists Practice Meditation?

The traditional Pure Land sutras are replete with contemplative exercises aimed at gaining visions of Amida Buddha and his Pure Land - for example, the Sutra on the Contemplation of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life (one of the canonical scriptures of the Pure Land tradition). Attaining such beatific visions through these often arduous practices was considered a sign of one's assurance of eventual enlightenment. In times closer to that of Shakyamuni, when the faithful transmission of contemplative practices from disciple to student was still intact, it was possible for some to gain a vision of the Buddha in this very life through a form of meditation called the Amitabha-samadhi. As this lineage of transmission now appears to have been broken, there are no longer any authentic teachers who can impart instruction in this form of meditation. Nevertheless, a number of Pure Land devotees today still resort to meditating on Amida with the aid of statues, paintings or mandalas in addition to those practices described in the sutras, as a way of expressing their joyful faith in the Buddha and his Dharma. Chief among such expressions, however, is the nembutsu or the invocation of the Sacred Name of Amida which, in itself, is a contemplative participation in the Buddha's Infinite Light.

The life of shinjin, as described in the previous chapter, is one of constant reflection on life and ourselves. This usually arises in an uncontrived manner as a natural consequence of being embraced by the Buddha's wisdom and compassion. The Shin Buddhist does not sit and practice hours of arduous meditation with a view to gaining enlightenment by one's own efforts. As the Pure Land tradition considers human spiritual capacity to be weak and defiled in this 'Decadent Age of the Dharma' (mappo), full enlightenment is not considered a possibility in this life where conditions for such attainment are viewed as extremely unfavourable. Accordingly, complete trust in Amida through shinjin is all that is required to realize Nirvana in the Pure Land where our enlightenment will be perfected and complete. This fact being assured to those with faith, all that remains to be done in this life is to express one's profound gratitude to the Buddha through the nembutsu and by living the Buddhist life to the best of one's ability.

One cannot, however, reach such a level of awareness without a certain degree of contemplative mindfulness of Amida Buddha as the supreme reality embracing all things. This can be considered as a kind of 'spontaneous' meditation in which one engages without any real effort. Such activity is not practiced with a view to any gain or 'results' but simply as a natural expression of the life of deep faith which is really a manifestation of the working of Amida's mind within us.

What is a Bodhisattva?

A bodhisattva is a being who seeks to attain enlightenment

in order to work towards the liberation of all beings from samsara. By the

unrelenting and tireless practice of the Buddhist virtues over many lifetimes,

the bodhisattva is able to achieve buddhahood but elects not to

pass into

complete Nirvana until he is able to ferry across all beings with him, however

long this may take. To this end, the bodhisattva is able to employ all the

transcendental powers of buddhahood to help and guide suffering beings by taking

their suffering upon himself and transferring his karmic merit to them. The

story of Dharmakara related earlier, is a classic example of the bodhisattva

path.

The bodhisattva path begins with the intention and desire to attain Nirvana for the sake of all beings (known as bodhicitta) and the taking of specific vows (pranidhana) aimed at giving effect to this aspiration. The traditional form of practice for bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism is known as the six paramitas or spiritual perfections. The first is dana which is the perfection of generosity and the readiness to give oneself up to the service of others - charity in the broadest sense. The second is shila which is the perfection of moral virtue and discipline. The third is kshanti which is the perfection of patience and forbearance. The fourth is virya which is the perfection of effort, vigour, heroism and strength. The fifth is dhyana which is the perfection of contemplation. The sixth is prajna which is the perfection of wisdom - the culmination and synthesis of all the other paramitas. Although these practices give the appearance of solely comprising individual effort, no success in such endeavours is ultimately possible without the helping and guiding power of the Buddha.

Mahayana Buddhism makes a distinction between two kinds of bodhisattvas. There is the earthly type which comprises people in the world whose good karma leads them to strive after enlightenment and to manifest compassion and altruism to all beings. The transcendent type of bodhisattva has already attained buddhahood but has chosen not to enter complete Nirvana until all beings are saved. Such beings are in possession of perfect wisdom and, unlike the other type, are no longer subject to the imperfections and limitations of samsara.

What is the role of bodhisattvas in Shin Buddhism ? From what has been said above, it is clear that people of shinjin fall into the first category of bodhisattvas insofar as they have aroused the aspiration of enlightenment which they expect to attain in the Pure Land in order to return as bodhisattvas of the transcendent type and help countless beings without hindrance. Until such time that they attain buddhahood after death, people of shinjin - despite their bodhicitta - still remain ordinary beings afflicted by the pain and uncertainties of human existence. Although such people can practice the six paramitas in a spontaneous and uncalculating act of gratitude, they can only do so in a limited and imperfect way because of the residual karmic ignorance and passions that still afflict them. Only Amida Buddha has perfectly fulfilled all the paramitas, the merits of which he fully bestows on those who take complete refuge in his saving power; a power that no merely human effort can hope to emulate.

Shin Buddhism, like all Mahayana schools, depends entirely on the theory and practice of the bodhisattva path because Dharmakara could not have transcended his own karmic evil without developing the paramitas and reaching Buddhahood - thus fulfilling his vows. More immediate, however, is the fact that Shinran was able to demonstrate that shinjin is bodhicitta as it is, in fact, Amida's Mind:

The mind that aspires to attain Buddhahood

Is the mind to save all sentient beings;

The mind to save all sentient beings

Is true and real shinjin, which is Amida's

benefitting of others.

(Hymns of the Pure Land Masters 18, et.al.)

So it is that people of shinjin may spontaneously behave in ways redolent with the qualities of the paramitas. However, there can be no expectation of such qualities as proof of shinjin. In Shinran's teaching, the status of the devotee as a bodhisattva is not stressed as the awareness of oneself as a 'foolish being' (Skt. prthagjana; Jap. bombu) is so prominent in the experience of shinjin, that it eclipses any practical claim to being a bodhisattva.

In Shin Buddhism, the act of returning to this world to assist sentient beings in gaining enlightenment after having attained it for oneself is known as genso eko.

The Law of Karma

Karma, which means, simply, "action" is fundamental to any understanding of Buddhism. In the Buddha's teaching, "the law of karma" is that all deliberate actions lead to results: good actions lead to pleasant results, bad actions to unpleasant results and so on. Shin Buddhism considers the law of karma to be inexorable and universal and absolutely rejects belief in divination and petitionary prayer.

Indeed, we have focussed almost entirely on the specific principles of Shin Buddhism but no school of Buddhism can be appreciated without a prior acquaintance with all of the basic ideas upon which Buddhism is founded.

Conclusion

We urge readers to examine the following essentials because, when viewed in isolation from them, a skewed view of Shin Buddhism will result: the Four Noble Truths; the Three Signata, namely, anatman or 'non-self', anitya or 'impermanence' and dukkha or 'suffering'; and, finally, Nirvana, which - as we have seen earlier - in Shin Buddhism is synonymous with Amida Buddha and the Pure Land. These are the teachings upon which Buddhism is grounded.

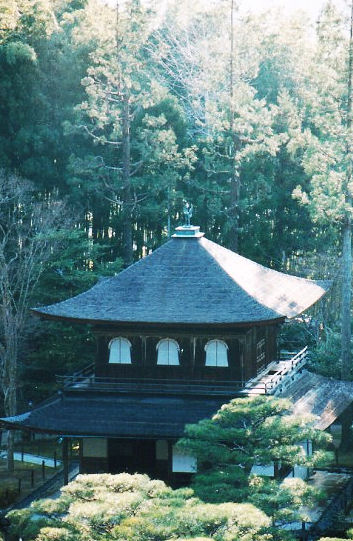

Photographs of Buddhist sites in Kyoto by Barry Leckenby.